Rolling (metalworking)

In metalworking, rolling is a metal forming process in which metal stock is passed through a pair of rolls. Rolling is classified according to the temperature of the metal rolled. If the temperature of the metal is above its recrystallization temperature, then the process is termed as hot rolling. If the temperature of the metal is below its recrystallization temperature, the process is termed as cold rolling. In terms of usage, hot rolling processes more tonnage than any other manufacturing process and cold rolling processes the most tonnage out of all cold working processes.[1][2]

There are many types of rolling processes, including flat rolling, foil rolling, ring rolling, roll bending, roll forming, profile rolling, and controlled rolling.

Contents |

Temperature

Hot rolling

Hot rolling is a metalworking process that occurs above the recrystallization temperature of the material. After the grains deform during processing, they recrystallize, which maintains an equiaxed microstructure and prevents the metal from work hardening. The starting material is usually large pieces of metal, like semi-finished casting products, such as slabs, blooms, and billets. If these products came from a continuous casting operation the products are usually fed directly into the rolling mills at the proper temperature. In smaller operations the material starts at room temperature and must be heated. This is done in a gas- or oil-fired soaking pit for larger workpieces and for smaller workpieces induction heating is used. As the material is worked the temperature must be monitored to make sure it remains above the recrystallization temperature. To maintain a safety factor a finishing temperature is defined above the recrystallization temperature; this is usually 50 to 100 °C (122 to 212 °F) above the recrystallization temperature. If the temperature does drop below this temperature the material must be re-heated before more hot rolling.[3]

Hot rolled metals generally have little directionality in their mechanical properties and deformation induced residual stresses. However, in certain instances non-metallic inclusions will impart some directionality and workpieces less than 20 mm (0.79 in) thick often have some directional properties. Also, non-uniformed cooling will induce a lot of residual stresses, which usually occurs in shapes that have a non-uniform cross-section, such as I-beams and H-beams. While the finished product is of good quality, the surface is covered in mill scale, which is an oxide that forms at high-temperatures. It is usually removed via pickling or the smooth clean surface process, which reveals a smooth surface.[4] Dimensional tolerances are usually 2 to 5% of the overall dimension.[5]

Hot rolling is used mainly to produce sheet metal or simple cross sections, such as rail tracks.

Cold rolling

Cold rolling occurs with the metal below its recrystallization temperature (usually at room temperature), which increases the strength via strain hardening up to 20%. It also improves the surface finish and holds tighter tolerances. Commonly cold-rolled products include sheets, strips, bars, and rods; these products are usually smaller than the same products that are hot rolled. Because of the smaller size of the workpieces and their greater strength, as compared to hot rolled stock, four-high or cluster mills are used.[2] Cold rolling cannot reduce the thickness of a workpiece as much as hot rolling in a single pass.

Cold-rolled sheets and strips come in various conditions: full-hard, half-hard, quarter-hard, and skin-rolled. Full-hard rolling reduces the thickness by 50%, while the others involve less of a reduction. Quarter-hard is defined by its ability to be bent back onto itself along the grain boundary without breaking. Half-hard can be bent 90°, while full-hard can only be bent 45°, with the bend radius approximately equal to the material thickness. Skin-rolling, also known as a skin-pass, involves the least amount of reduction: 0.5-1%. It is used to produce a smooth surface, a uniform thickness, and reduce the yield-point phenomenon (by preventing Luder bands from forming in later processing).[6] It is also used to breakup the spangles in galvanized steel. Skin-rolled stock is usually used in subsequent cold-working processes where good ductility is required.[2]

Other shapes can be cold-rolled if the uniform is relatively uniform and the transverse dimension is relatively small; approximately less than 50 mm (2.0 in). This may be a cost-effective alternative to extruding or machining the profile if the volume is in the several tons or more. Cold rolling shapes requires a series of shaping operations, usually along the lines of: sizing, breakdown, roughing, semi-roughing, semi-finishing, and finishing.[2]

Processes

Flat rolling

Flat rolling is the most basic form of rolling with the starting and ending material having a rectangular cross-section. The material is fed in between two rollers, called working rolls, that rotate in opposite directions. The gap between the two rolls is less than the thickness of the starting material, which causes it to deform. The decrease in material thickness causes the material to elongate. The friction at the interface between the material and the rolls causes the material to be pushed through. The amount of deformation possible in a single pass is limited by the friction between the rolls; if the change in thickness is too great the rolls just slip over the material and do not draw it in.[1] The final product is either sheet or plate, with the former being less than 6 mm (0.24 in) thick and the latter greater than; however, heavy plates tend to be formed using a press, which is termed forming, rather than rolling.

Oftentimes the rolls are heated to assist in the workability of the metal. Lubrication is often used to keep the workpiece from sticking to the rolls. To fine tune the process the speed of the rolls, the roller resistance, and the temperature of the rollers are adjusted.[7]

Foil rolling

Foil rolling is a specialized type of flat rolling, specifically used to produce foil, which is sheet metal with a thickness less than 200 µm (0.0079 in). The rolling is done in a cluster mill because the small thickness requires a small diameter rolls.[3] To reduce the need for small rolls pack rolling is used, which rolls multiple sheets together to increase the effective starting thickness. As the foil sheets come through the rollers, they are trimmed and slitted with circular or razor-like knives. Trimming refers to the edges of the foil, while slitting involves cutting it into several sheets.[7] Aluminum foil is the most commonly produced product via pack rolling. This is evident from the two different surface finishes; the shiny side is on the roll side and the dull side is against the other sheet of foil.[8]

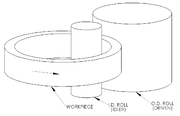

Ring rolling

Ring rolling is a specialized type of hot rolling that increases the diameter of a ring. The starting material is a thick-walled ring. This workpiece is placed on an idler roll, while another roll, called the driven roll, presses the ring from the outside. As the rolling occurs the wall thickness decreases as the diameter increases. The rolls may be shaped to form various cross-sectional shapes. The resulting grain structure is circumferential, which gives better mechanical properties. Diameters can be as large as 8 m (26 ft) and face heights as tall as 2 m (79 in). Common applications include rockets, turbines, airplanes, pipes, and pressure vessels.[4]

Roll bending

Roll bending produces a cylindrical shaped product from plate or steel metal.[9]

Roll forming

Roll forming is a continuous bending operation in which a long strip of metal (typically coiled steel) is passed through consecutive sets of rolls, or stands, each performing only an incremental part of the bend, until the desired cross-section profile is obtained. Roll forming is ideal for producing parts with long lengths or in large quantities.

Structural shape rolling

Controlled rolling

Controlled rolling is a type of thermomechanical processing which integrates controlled deformation and heat treating. The heat which brings the workpiece above the recrystallization temperature is also used to perform the heat treatments so that any subsequent heat treating is unnecessary. Types of heat treatments include the production of a fine grain structure; controlling the nature, size, and distribution of various transformation products (such as ferrite, austenite, pearlite, bainite, and martensite in steel); inducing precipitation hardening; and, controlling the toughness. In order to achieve this the entire process must be closely monitored and controlled. Common variables in controlled rolling include the starting material composition and structure, deformation levels, temperatures at various stages, and cool-down conditions. The benefits of controlled rolling include better mechanical properties and energy savings.[5]

Mills

A rolling mill, also known as a reduction mill or mill, has a common construction independent of the specific type of rolling being performed:[10]

- Work rolls

- Backup rolls - are intended to provide rigid support required by the working rolls to prevent bending under the rolling load

- Rolling balance system - to ensure that the upper work and back up rolls are maintain in proper position relative to lower rolls

- Roll changing devices - use of an overhead crane and a unit designed to attach to the neck of the roll to be removed from or inserted into the mill.

- Mill protection devices - to ensure that forces applied to the backup roll chocks are not of such a magnitude to fracture the roll necks or damage the mill housing

- Roll cooling and lubrication systems

- Pinions - gears to divide power between the two spindles, rotating them at the same speed but in different directions

- Gearing - to establish desired rolling speed

- Drive motors - rolling narrow foil product to thousands of horsepower

- Electrical controls - constant and variable voltages applied to the motors

- Coilers and uncoilers - to unroll and roll up coils of metal

Slabs are the feed material for hot strip mills or plate mills and blooms are rolled to billets in a billet mill or large sections in a structural mill. The output from a strip mill is coiled and, subsequently, used as the feed for a cold rolling mill or used directly by fabricators. Billets, for re-rolling, are subsequently rolled in either a merchant, bar or rod mill. Merchant or bar mills produce a variety of shaped products such as angles, channels, beams, rounds (long or coiled) and hexagons.

Configurations

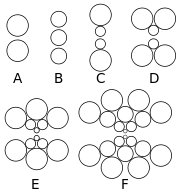

Mills are designed in different types of configurations, with the most basic being a two-high non-reversing, which means there are two rolls that only turn in one direction. The two-high reversing mill has rolls that can rotate in both directions, but the disadvantage is that the rolls must be stopped, reversed, and then brought back up to rolling speed between each pass. To resolve this, the three-high mill was invented, which uses three rolls that rotate in one direction; the metal is fed through two of the rolls and then returned through the other pair. The disadvantage to this system is the workpiece must be lifted and lowered using an elevator. All of these mills are usually used for primary rolling and the roll diameters range from 60 to 140 cm (24 to 55 in).[3]

To minimize the roll diameter a four-high or cluster mill is used. A small roll diameter is advantageous because less roll is in contact with the material, which results in a lower force and energy requirement. The problem with a small roll is a reduction of stiffness, which is overcome using backup rolls. These backup rolls are larger and contact the back side of the smaller rolls. A four-high mill has four rolls, two small and two large. A cluster mill has more than 4 rolls, usually in three tiers. These types of mills are commonly used to hot roll wide plates, most cold rolling applications, and to roll foils.[3]

Historically mills were classified by the product produced:[11]

- Blooming, cogging and slabbing mills, being the preparatory mills to rolling finished rails, shapes or plates, respectively. If reversing, they are from 34 to 48 inches in diameter, and if three-high, from 28 to 42 inches in diameter.

- Billet mills, three-high, rolls from 24 to 32 inches in diameter, used for the further reduction of blooms down to 1.5x1.5-inch billets, being the preparatory mills for the bar and rod

- Beam mills, three-high, rolls from 28 to 36 inches in diameter, for the production of heavy beams and channels 12 inches and over.

- Rail mills with rolls from 26 to 40 inches in diameter.

- Shape mills with rolls from 20 to 26 inches in diameter, for smaller sizes of beams and channels and other structural shapes.

- Merchant bar mills with rolls from 16 to 20 inches in diameter.

- Small merchant bar mills with finishing rolls from 8 to 16 inches in diameter, generally arranged with a larger size roughing stand.

- Rod and wire mills with finishing rolls from 8 to 12 inches in diameter, always arranged with larger size roughing stands.

- Hoop and cotton tie mills, similar to small merchant bar mills.

- Armour plate mills with rolls from 44 to 50 inches in diameter and 140 to 180-inch body.

- Plate mills with rolls from 28 to 44 inches in diameter.

- Sheet mills with rolls from 20 to 32 inches in diameter.

- Universal mills for the production of square-edged or so-called universal plates and various wide flanged shapes by a system of vertical and horizontal rolls.

Tandem mill

A tandem mill is a special type of modern rolling mill where rolling is done in one pass. In a traditional rolling mill rolling is done in several passes, but in tandem mill there are several stands and reductions take place successively. The number of stands ranges from 2 to 18. Tandem mill can be either hot or cold rolling mill type.

Defects

In hot rolling, if the temperature of the workpiece is not uniform the flow of the material will occur more in the warmer parts and less in the cooler. If the temperature difference is great enough cracking and tearing can occur.[3]

Flatness

Maintaining a uniform gap between the rolls is difficult because the rolls deflect under the load required to deform the workpiece. The deflection causes the workpiece to be thinner on the edges and thicker in the middle. This can be overcome by using a crowned roller, however the crowned roller will only compensate for one set of conditions, specifically the material, temperature, and amount of deformation. If the flatness defect is great enough the edges will become wavy or the center may produce fractures.[5]

Another way to overcome defection issues is by decreasing the load on the rolls, which can be done by applying an longitudinal force; this is essentially drawing. Other method of decreasing roll defection include increasing the elastic modulus of the roll material and adding back-up supports to the rolls.[5]

Surface defects

There are six types of surface defects:[12]

- Lap

- This type of defect occurs when a flap of is folded over and rolled but not welded into the metal. They appear as seams across the surface of the metal.

- Mill-shearing

- These defects occur as a feather like lap.

- Rolled-in scale

- This occurs when mill scale is rolled into metal.

- Scabs

- These are long patches of loose metal that have been rolled into the surface of the metal.

- Seams

- They are open, broken lines that run along the length of the metal and caused by the presence of scale.

- Slivers

- Prominent surface ruptures.

History

Iron and steel

The earliest rolling mills were slitting mills, which were introduced from what is now Belgium to England in 1590. These passed flat bars between rolls to form a plate of iron, which was then passed between grooved rolls (slitters) to produce rods of iron. The first experiments at rolling iron for tinplate took place about 1670. In 1697, Major John Hanbury erected a mill at Pontypool to roll 'Pontypool plates'—blackplate. Later this began to be rerolled and tinned to make tinplate. The earlier production of plate iron in Europe had been in forges, not rolling mills.

The slitting mill was adapted to producing hoops (for barrels) and iron with a half-round or other sections by means that were the subject of two patents of c. 1679.

Some of the earliest literature on rolling mills can be traced back to Christopher Polhem in 1761 in Patriotista Testamente, where he mentions rolling mills for both plate and bar iron.[13] He also explains how rolling mills can save on time and labor because a rolling mill can produce 10 to 20 and still more bars at the same time which is wanted to tilt only one bar with a hammer.

A patent was granted to Thomas Blockley of England in 1759 for the polishing and rolling of metals. Another patent was granted in 1766 to Richard Ford of England for the first tandem mill.[14] A tandem mill is one in which the metal is rolled in successive stands; Ford’s tandem mill was for hot rolling of wire rods.

Other metals

Rolling mills for lead seem to have exited by the late 17th century. Copper and brass were also rolled by the late 18th century.

Modern rolling

The modern rolling practice can be contributed to the efforts of Henry Cort of Fontley Iron Mills, near Fareham, England. In 1783 a patent was issued to Henry Cort for his use of grooved rolls for rolling iron bars.[15] With this new design mills were able to produce 15 times the output per day than with a hammer.[16] Although Cort was not the first to use grooved rolls; he was the first to combine the use of all the best features of various ironmaking and shaping processes known at the time. Thus the term “father of modern rolling” was giving to him by modern writers.

The first rail rolling mill was established by John Birkenshaw in 1820 where he produced fish bellied wrought iron rails in lengths of 15 to 18 feet.[16] With the advancement of technology in rolling mills the size of rolling mills grew rapidly along with the size products being rolled. Example of this was at The Great Exhibition in 1851 a plate 20 feet long, 3 ½ feet wide, and 7/16 of inch thick, weighed 1,125 pounds was exhibited by the Consett Iron Company.[16] Further evolution of the rolling mill came with the introduction of Three-high mills in 1853 used for rolling heavy sections.

See also

- Bernard Lauth

- John B. Tytus

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 384.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 408.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 385.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 387.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 388.

- ↑ It locks dislocations at the surface and thereby reduces the possibility of formation of Luders bands. To avoid Luders bands formation it is necessary to create substantial density of unpinned dislocations in ferrite matrix.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 http://www.enotes.com/how-products-encyclopedia/aluminum-foil

- ↑ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 386.

- ↑ Todd, Robert H.; Allen, Dell K.; Alting, Leo (1994), Manufacturing Processes Reference Guide, Industrial Press Inc., pp. 300–304, ISBN 0-8311-3049-0, http://books.google.com/books?id=6x1smAf_PAcC.

- ↑ Roberts 1978, p. 64.

- ↑ Kindl, F. H. (1913), The Rolling Mill Industry, Penton Publishing, pp. 13–19, http://books.google.com/books?id=EIhAAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA13.

- ↑ Definition of standard mill terms, archived from the original on 03-04-2010, http://www.webcitation.org/5nzOUAsA3, retrieved 03-04-2010.

- ↑ Swank, James M., History of the Manufacturers of Iron in All Ages, Published by Burt Franklin 1892, p.91

- ↑ Roberts 1978, p. 5.

- ↑ R. A. Mott (ed. P. Singer), Henry Cort: the great finer (Metals Society, London 1983), 31-36; English patents, nos. 1351 and 1420.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Roberts 1978, p. 6.

Bibliography

- Degarmo, E. Paul; Black, J T.; Kohser, Ronald A. (2003), Materials and Processes in Manufacturing (9th ed.), Wiley, ISBN 0-471-65653-4.

- Roberts, William L. (1978), Cold Rolling of Steel, Marcel Dekker, ISBN 9780824767808, http://books.google.com/books?id=nOrdxdGe8T8C.

Further reading

- Roberts, William L. (1983), Hot Rolling of Steel, CRC Press, ISBN 9780824713454, http://books.google.com/books?id=pqt_DwrJcXIC.

- Ginzburg, Vladimir B.; Ballas, Robert (2000), Flat Rolling Fundamentals, CRC Press, ISBN 9780824788940, http://books.google.com/books?id=NeKG76F4KWUC.

- Lee, Youngseog (2004), Rod and bar rolling, CRC Press, ISBN 9780824756499, http://books.google.com/books?id=ua_m3_sKOwYC.

- Swank, James M. (1965), History of the Manufacture of Iron in All Ages (2nd ed.), Ayer Publishing, ISBN 9780833734631, http://books.google.com/books?id=xkVPNtRagDkC.

- Reed-Hill, Robert, et al. "Physical Metallurgy Principles", 3rd Edition, PWS publishing, Boston, 1991. ISBN 978-0534921736.

- Callister Jr., William D., "Materials Science and Engineering - an Introduction", 6th Edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York, Ny, 2003. ISBN 0-471-13576-3

External links

- How Liners Achieve the Desired Quality of the Product Being Rolled

- NSW HSC Description of Rolling

- History of Rolling Mills

- Key to metals: Steel Rolling

|

||||||||||||||||||||||